Disclosure: This should not be considered as evidence-based mental health literature. These are the observations of a surgeon with extensive experience being angry.

Introduction

Many physicians are finding themselves strained from ongoing sociopolitical crises. Dealing with the frequent or continuous consequences of unsustainable practices in health care systems, global systems issues like racism or sexism, or other large problems that are difficult to impossible for an individual to fix, can incite negative emotions. Like rage. Rage is often triggered by a deep sense of unfairness, disappointment, or lack of safety in a situation. It is not an easy thing to turn off. It may change in intensity and type, but in the setting of continuous triggers, rage can become a cycle.

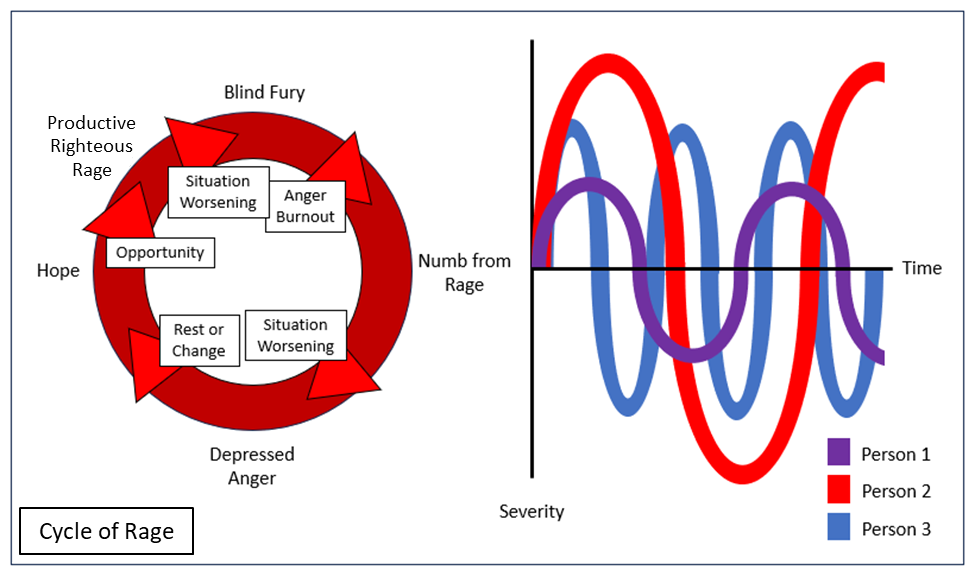

Rage can sometimes be a great motivator, but when it becomes a chronic state it is associated with multiple health risks including hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and injuries from motor vehicle collisions. To reduce these effects, several schools of psychology and philosophy emphasize the importance of avoiding perseveration on things we can’t control. With the corporatization of medical systems and a shift away from prioritizing equity and independent integrity of scientific data and health care, it seems many aspects of our environments are decreasingly responsive to our influence. How to get out of the cycle of rage is beyond the scope of this article, but recognizing it may be helpful. Recognition is important not only in ourselves but also in our colleagues. Trauma bonding is a common phenomenon in practice and training. There are benefits from these bonds, but they can also leave people in a group vulnerable to the effects of each other’s position in the cycle of rage (see image above).

The description of this cycle is based on personal and professional observations during difficult situations affecting groups of people, all of whom have gone through this cycle at different rates and frequencies, with different external manifestations. My hope is that by naming and identifying the cycle of rage in themselves and colleagues, readers will be encouraged to work to escape it while being generous with grace.

The cycle

Productive righteous rage

This is usually the least destructive phase of the cycle. When a physician recognizes a problem or a flaw in the system, the default response for many of us is: “How do I fix this?” Outside of the cycle and for solvable problems, rage can be an effective tool for productivity. For example, when trainees are struggling with coming up with QI or research topics I often advise them to write down everything that makes them angry for one to two weeks; there is usually a research question in that list. However, when the problem does not have a solution or a solution within your control, rage is an ineffective tool and can be harmful. Using rage as a motivator in these situations can lead to long-lasting and maladaptive sympathetic activation; the long-term stress response and hypervigilance may leave you vulnerable to the physical and mental health consequences as well as entering the next stage of the cycle of rage, particularly if external conditions worsen.

Blind rage

This stage is the most externally damaging phase and is characterized by a prolonged extreme stress response with a fight-or-flight hypervigilance and hyperreactivity. People in this phase tend to have a difficult time controlling their emotions and their reactions to negative external stimuli. They may find themselves having angry outbursts. The professional filter most people normally have in place is damaged or destroyed. Even for people without a history of such outbursts, unfiltered reactions to enraging situations and people can lead to permanent damage to your reputation and relationships with others. Rage responses in this phase consume a lot of energy and can lead to the next stage, numbness.

Numbness

The body and mind can only spend so much time in a constant rage state before breaking down. This may mean developing a severe physical problem that takes all attention and energy away from the source of rage, or it may mean shutting down emotionally. This state is similar to and possibly related to adrenal fatigue. Numbness is not a productive phase, and this lack of emotional energy may cause problems in personal relationships.

Depressed rage

Like local anesthesia, when numbness wears off what is uncovered is usually pain. It may feel like sadness, disappointment, grief, or may lead to an actual clinical depression, particularly with the loss of agency associated with remaining in a situation with a solution-less problem. Depression can lead to physical health issues, substance use disorders, and risk for suicide. This stage can be the most internally damaging. If you find that you or one of your partners is struggling with this phase, it is important to seek help.

Hope

Hope could be thought of as a positive part of the cycle. Entry into this phase may follow a rest with renewal of energy or situational change leading to an opportunity to solve a previously unsolvable problem, such as a new manager, idea, or other resource. If the problem somehow becomes one with a solution within your control, hope may allow progression into the productive righteous rage phase. If the problem is truly solvable, this has the potential to accelerate out of the cycle by fixing the actual rage trigger. If the problem remains without a solution, hope, when false, can be blinding. It may bring you out of the more self-destructive phases of the cycle, but without a change in the problem or situation, you remain stuck within it.

Group cycling

The cycle of rage rarely exists in isolation, and one can enter the cycle at any stage depending on the individual response to the situation triggering the entrance. Even if multiple people in a group enter the cycle at the same stage, their amplitude and cycle length rarely line up perfectly (see image above). In groups who work together closely, this can lead to interpersonal conflict as coping mechanisms, insight, and bandwidth for empathy vary and clash. There is no fountain of mental health and emotional energy to magically fix a group of people in the cycle of rage. Pizza doesn’t fix it either. Recognition, grace, and support are vital to survive the triggering situation and the cycle of rage with relationships intact.

Situational rage

The cycle of rage can be compartmentalized to a specific part of your life or work. If you have a boss who is terrible but seemingly immune to consequence, you may only feel the effects of the cycle when you interact with them or deal with downstream effects of their actions. If your rage is triggered by sexism, you may only feel the consequences of the cycle when you are met with the effects of sexism. The damage in these cases may be less overall, but if you are in the cycle of rage it may be difficult to control your response to these triggers when they arise. Compartmentalizing the cycle rather than working on a way out may compound the power of those triggers and lead to explosive consequences. Unfortunately, compartmentalizing rage is not the same as getting out of the cycle.

Getting out

How to remove yourself from maladaptive coping patterns such as the cycle of rage is a topic with centuries’ worth of articles, books, and other references to choose from. The strategies therein are often complex, time-consuming, and imperfect. There is no one approach that works for everyone, and any method that works for you will require work and have imperfect results. Even stoic philosophy, which emphasizes the importance of self-control, wasn’t executed effortlessly or perfectly by its originators. Whether it’s CBT, meditation, or other methods, getting out of the cycle requires work, perseverance, discipline, and the ability to accept help when it’s needed.

Conclusion

Managing ourselves in a world where our influence is frustratingly limited in the face of major problems is getting harder, and terms like “burnout” with complex connotations are sometimes unhelpful. The cycle of rage is a pattern of response to solution-less problems that can be extremely harmful. Recognizing this cycle in ourselves can help identify the need for a way out of the cycle, guided by whichever psychological, philosophical, or lifestyle-changing approach works for you. Recognizing the cycle of rage in our colleagues can help frame incongruent reactions to situations and interpersonal conflict and allow us to better support each other.

We are angry. Our rage is often justified, as is that of our peers. However, we must be able to recognize the cycle of rage so we can work on getting ourselves out.

Alexandra M.P. Brito and Jennifer L. Hartwell are surgeons.

![AI censorship threatens the lifeline of caregiver support [PODCAST]](https://kevinmd.com/wp-content/uploads/Design-2-190x100.jpg)