Suicide is the elephant in the room in medicine. We rarely speak about it openly, yet it remains a silent epidemic, among our patients, and tragically, among physicians themselves.

I first encountered this reality as a medical student in Tennessee in 2022. One of my earliest patients was not much younger than I was. Because we were close in age, I felt we connected quickly. We spoke about his struggles, and I thought I was helping him. But what lay beneath the surface was something I could not see.

One day, he stopped coming to clinic. Weeks later, I learned from his family that he had taken his own life. The news left me stunned. I replayed every conversation, every visit. Could I have done something differently? Was there something I missed? The guilt of losing a patient in this way is not easily put into words. It leaves a mark.

There was one detail that has stayed with me: We shared a love of Japanese anime and culture. During medical school, I made a lighthearted promise (a bet with classmates) that I would learn Japanese, no matter how difficult. At the time, it was a joke. After my patient’s death, it became something more: a way to honor him.

On the first anniversary of his death, I traveled to Japan for a medical elective. What began as an act of remembrance turned into a new direction for my life and career. I returned again and again, eventually moving here to work as a medical researcher and pursue a Japanese medical license.

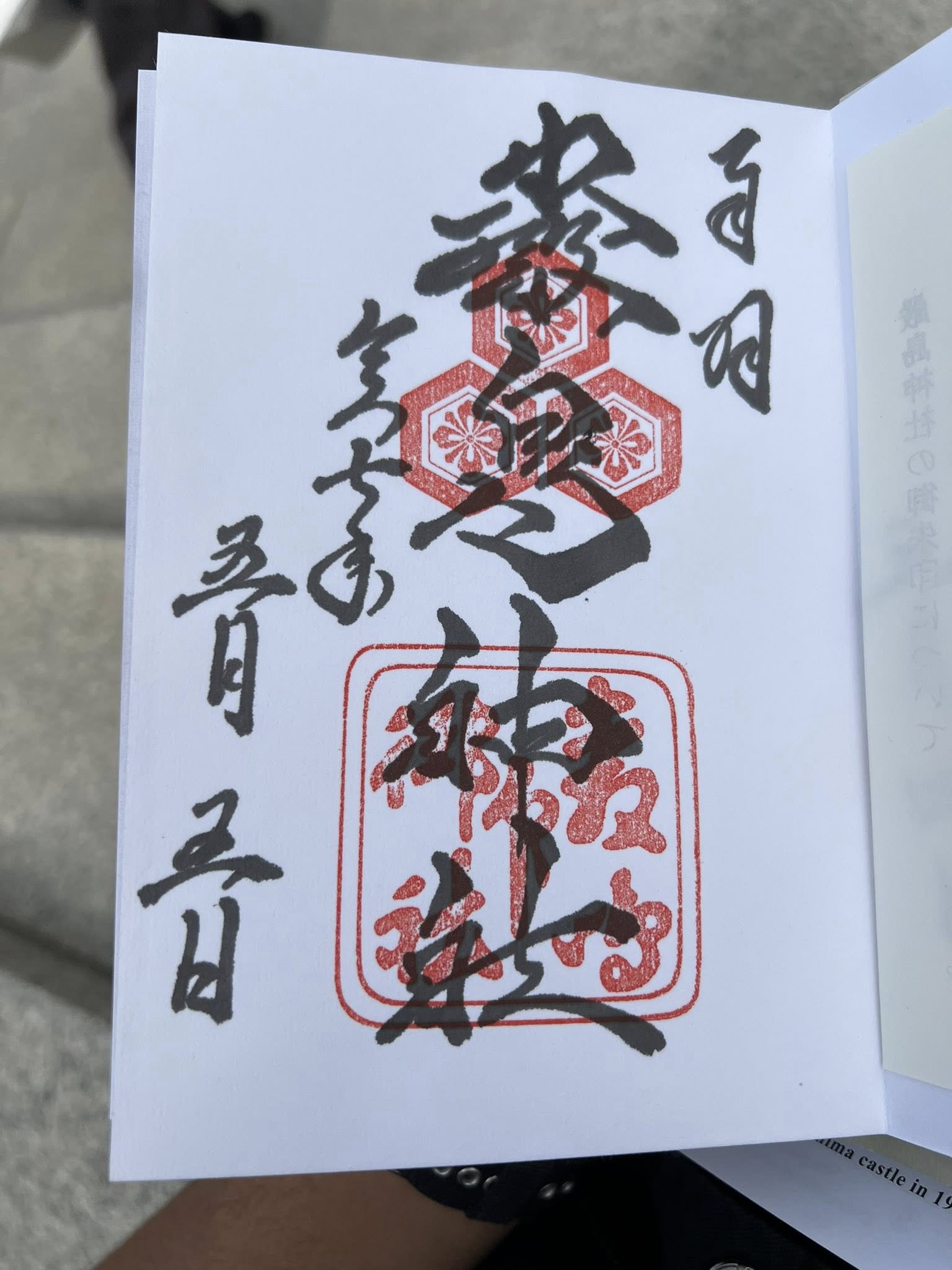

Along the way, I began collecting goshuin, hand-drawn calligraphy stamps from temples and shrines across Japan. At first, it was a way to cope with grief, a personal ritual of healing. But over time, it became a journey that carried me from Hokkaido’s snow-filled fields to the shrines of Hiroshima and Osaka, from quiet mountain temples to bustling city centers. Each stamp symbolized not only a sacred space but also a step forward in finding peace, closure, and purpose.

In medicine, we are trained to look for diagnoses, lab results, and protocols. What we are not always trained for is how to sit with grief: our patients’, our colleagues’, or our own. Learning Japanese, walking temple paths, and filling page after page of goshuin was my way of grappling with the reality of a patient’s suicide. It gave me a new lens of empathy and connection with others who struggle silently.

But as physicians, we cannot stop at personal healing. We must confront the broader issue. Suicide among patients is devastating, but suicide among physicians is a crisis as well. Doctors die by suicide at higher rates than the general population, yet stigma and silence persist. We hesitate to seek help, fearing judgment, licensure repercussions, or being seen as weak. Too often, this silence is fatal.

In Japan, I have come to see how culture can shape approaches to grief and resilience. Practices like goshuin collecting or calligraphy (shodō) provide outlets for meaning, reflection, and presence. They are not solutions by themselves, but they point to something medicine everywhere needs more of: spaces for healing that go beyond checklists and metrics.

Looking back, I realize that promise I made in medical school (to learn Japanese) was never just about language. It was about finding a way to carry forward a patient’s memory, to transform grief into growth, and to face the unspoken realities of mental health in our profession.

We need more open conversations about suicide, both in patients and among doctors. Silence saves no one. By sharing our stories, however painful, we honor those we have lost and remind each other that healing is possible, not only for our patients, but for ourselves. Every goshuin stamp I carry is a reminder: of a patient whose voice is gone, of a promise I am still keeping, and of the work we must all continue to do to confront suicide in medicine.

Vikram Madireddy is a neurologist.

![AI censorship threatens the lifeline of caregiver support [PODCAST]](https://kevinmd.com/wp-content/uploads/Design-2-190x100.jpg)