The story of gastroenterology in 2025 is no longer about productivity or reimbursement; it’s about manpower. Hospitals and practices across the U.S. are struggling to recruit, retain, or even temporarily staff the specialists who manage digestive diseases, perform colon cancer screening, and handle emergency procedures like ERCP. What we’re facing isn’t simply a staffing issue; it’s a structural shortage decades in the making.

The shrinking pipeline of gastroenterologists

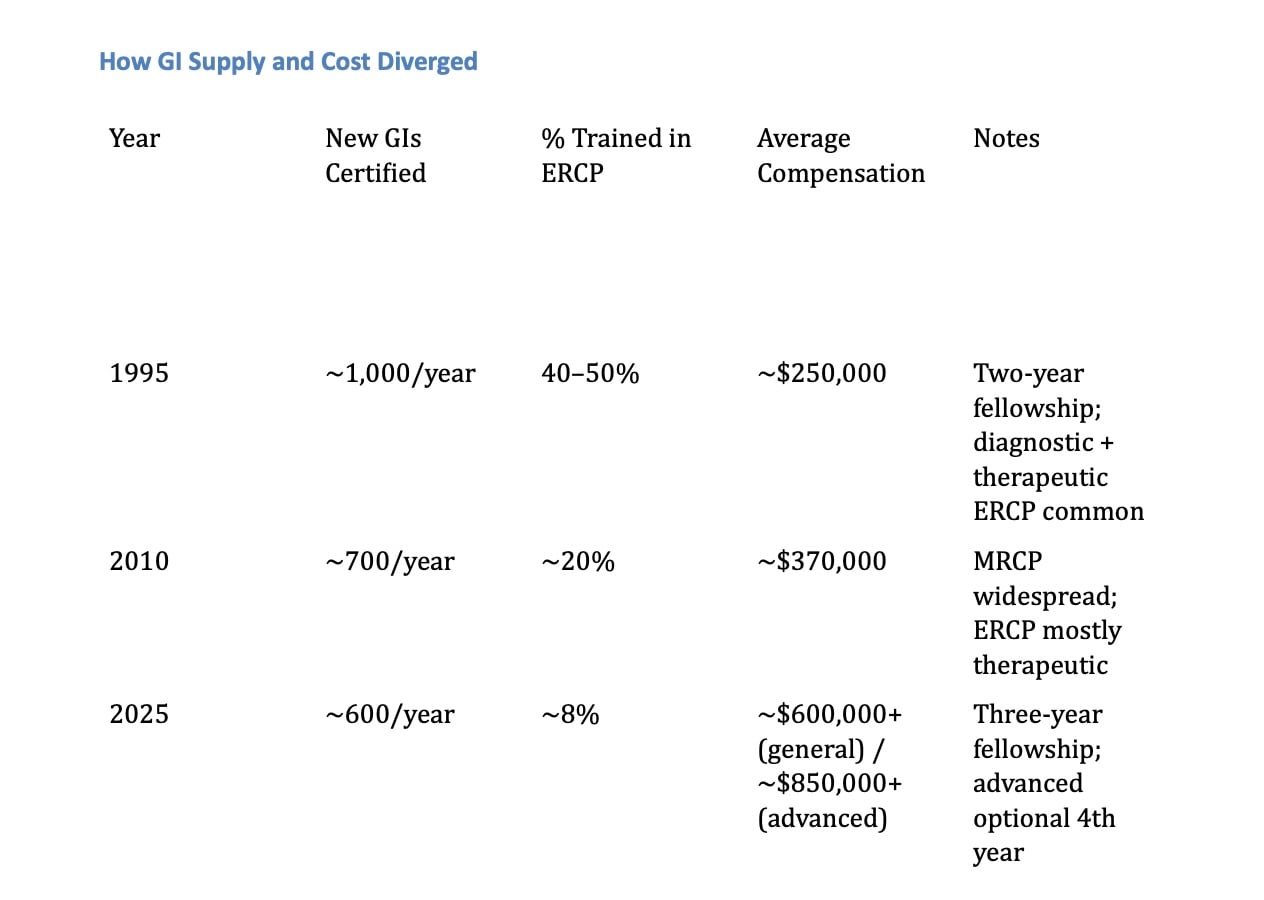

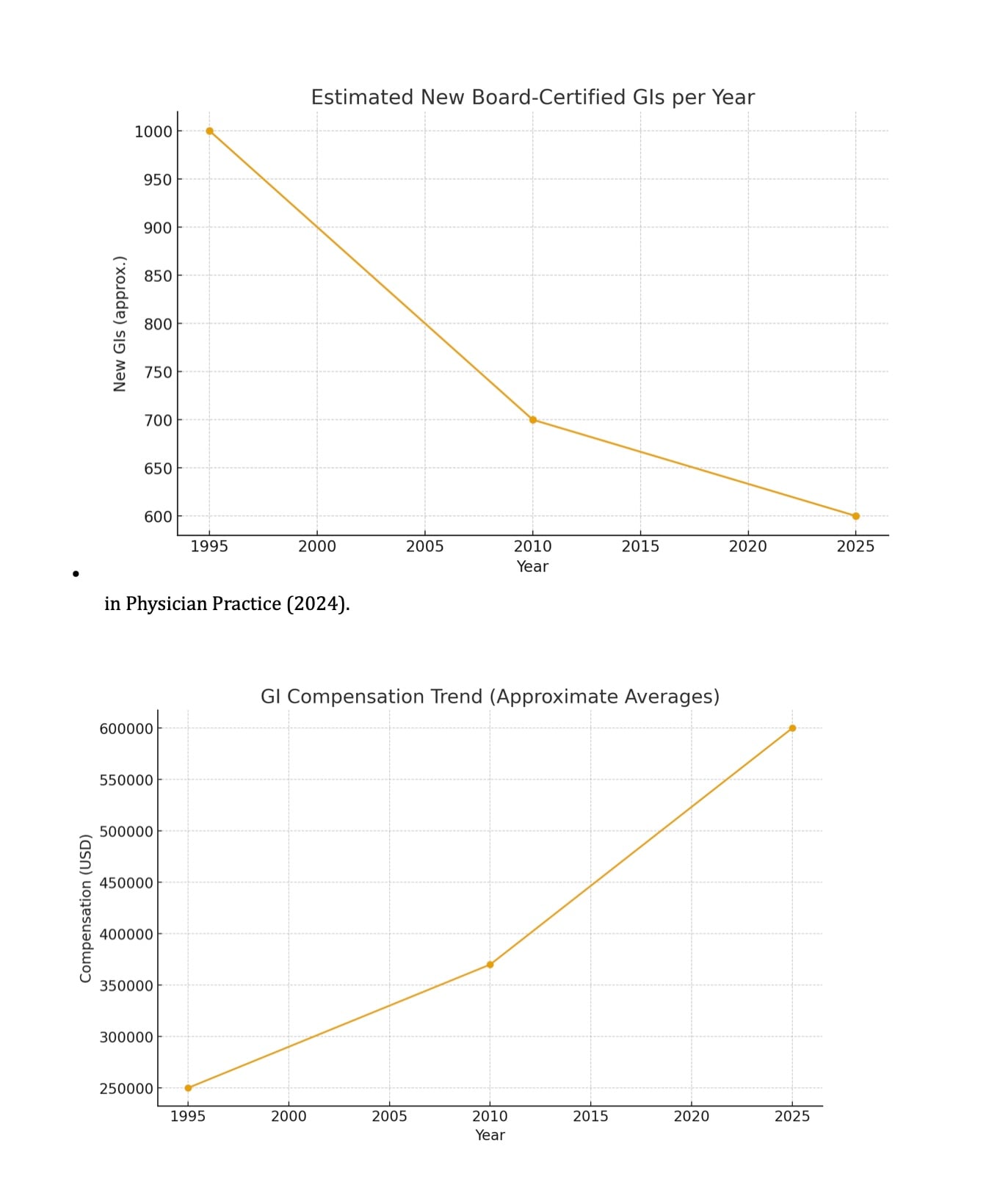

In the mid-1990s, roughly 1,000 new gastroenterologists were board-certified each year. Today, that figure has fallen to about 600 annually, a nearly 40 percent drop despite an aging population and surging procedural demand. This contraction can be traced back to a critical policy shift: In 1994, fellowship training in gastroenterology was lengthened from two years to three, and advanced procedures like ERCP (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography) and EUS (endoscopic ultrasound) were spun off into a separate one-year advanced endoscopy fellowship. However, funding for new training positions was never increased, as Medicare’s GME caps remained frozen since 1997. At the time, leaders believed the field was facing oversupply, an assumption that proved disastrously wrong. The same cohort of physicians trained during that period are now in their early 60s, and many are beginning to retire. The math is stark: When about 1,000 doctors per year entered practice, the system held steady. Now, with only 600 new GIs entering the workforce to replace an aging cohort of 1,000 retiring or scaling back, the net workforce deficit grows by roughly 400 gastroenterologists per year. Ongoing demands by the ABIM for MOC and recertification is pushing more of our aging gastroenterologists to just say enough is enough and retiring earlier than they otherwise would have.

From diagnostic to therapeutic: the ERCP evolution

In the 1980s and early 1990s, 40-50 percent of gastroenterologists were trained in ERCP. Back then, ERCP served both diagnostic and therapeutic roles, visualizing the bile and pancreatic ducts before high-resolution imaging existed. The late 1990s brought MRCP (magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography), which replaced most diagnostic ERCPs with noninvasive imaging. Today, only about 8 percent of newly trained gastroenterologists perform ERCP, which now serves an exclusively therapeutic role. The combination of longer training, higher complexity, and static fellowship funding created a bottleneck for therapeutic endoscopists.

An aging workforce and rising demand

Nearly half of active gastroenterologists are now over 55 years old. As they retire or move to part-time work, the replacement rate lags behind. Meanwhile, colorectal screening starting at age 45 and rising liver disease prevalence have accelerated patient demand. A 2025 Weill Cornell Medicine report found that nearly 50 million Americans live more than 25 miles from a gastroenterologist.

The economics of scarcity

Compensation data illustrates the growing imbalance:

- 2015: ~$370,000 average GI salary.

- 2020: ~$417,000.

- 2023-2024: ~$514,000 (35 percent increase).

- 2025: $600,000+ for general GI; $800,000-$900,000+ for ERCP/EUS-trained.

Unlike a decade ago, new GI recruits now demand permanent salary guarantees instead of temporary income floors. Hospitals, once beneficiaries of higher facility fee negotiations, now find themselves paying far more to retain or recruit physicians.

Locum coverage: the cost of delay

Locum tenens coverage is now the fallback option for hospitals unable to recruit permanent physicians:

- Outpatient only: $400-$450/hour.

- Inpatient with call: $450-$500+/hour or $3,000-$4,500/day.

- Advanced ERCP/EUS: $500-$600+/hour, often $4,000-$5,500/day.

With agency markups, malpractice, and travel costs, hospitals pay $7,000-$8,000/day for coverage.

Private equity’s role

Private equity-backed consolidation of GI practices has restructured outpatient care and withdrawn many physicians from hospital call. Hospitals, forced to hire or contract independently, face escalating costs and worsening workforce shortages.

Flat reimbursement, rising costs

Even as labor costs rise, Medicare’s Physician Fee Schedule has declined more than 30 percent in real dollars since 2001. Private payers tethered to Medicare rates have followed suit, leaving hospitals paying more for the same work.

The forecast: The shortage grows every year

With only 600 new GIs certified annually and the youngest doctors from the 1990s now in their 60s, the deficit grows by roughly 400 doctors per year. Within five years, the U.S. could face a 20 percent shortfall, over 3,000 gastroenterologists.

What must change

- Expand GI and advanced endoscopy fellowships under Medicare GME, prioritizing underserved regions.

- Reform reimbursement to recognize procedural risk, on-call burden, and inflation.

- Retain senior physicians through simplified maintenance pathways and flexible call sharing.

- Stabilize hospital-ASC collaboration rather than perpetuating adversarial models.

- Invest in multidisciplinary GI care teams, including APPs and tele-endoscopy programs.

Conclusion

The gastroenterology shortage is not cyclical; it’s structural. It began when training slowed, funding froze, and procedural complexity outpaced workforce planning. Now, hospitals are competing in a seller’s market, paying salaries that once seemed unthinkable, not out of excess, but necessity. Until training capacity expands and compensation aligns with reality, one fact will remain: The only thing more expensive than hiring a gastroenterologist is not having one at all.

Brian Hudes is a gastroenterologist.

![AI censorship threatens the lifeline of caregiver support [PODCAST]](https://kevinmd.com/wp-content/uploads/Design-2-190x100.jpg)