We’re constantly reminded of the organ shortage and the lives lost while waiting for a kidney. Like fish unaware they swim in water, we’ve accepted the rising tide of kidney failure as natural and inevitable, but it’s not. The most urgent question goes unasked: Why do so many kidneys fail?

Diabetes is the leading cause of kidney failure, with 40 percent of those on the kidney waitlist diabetic. Every day in the U.S. 170 diabetic patients begin dialysis or have a kidney transplant; that’s 62,000 people a year.

Medicare spends a staggering $50 billion annually on dialysis and transplantation through the Medicare End Stage Renal Disease Program (1972), which extends Medicare coverage for anyone with kidney failure, regardless of age. Although only 1 percent of Medicare patients have kidney failure, their care accounts for 7 percent of the Medicare budget.

Diabetes prevalence is surging. Today, 34 million adults in the U.S. are diabetic, a number projected to surge to nearly 55 million by 2030. Over a third will develop diabetic kidney disease, fueling new kidney failure cases and Medicare spending for dialysis and transplantation.

The 2030 projected annual cost of care related to diabetes and comorbidities? An unsustainable $622 billion, up 53 percent since 2015. This isn’t a future crisis. It’s happening now.

Medicaid: first line of defense

Under the Americans with Disabilities Act, diabetes is recognized as a disabling condition. When prevention and early treatment are neglected, young people face decades of illness and complications — including kidney failure, heart disease, vision loss, amputation, and chronic pain. Ultimately, we all bear the high cost of treating kidney failure.

One in six Americans – 15.8 percent – are diabetic. Medicaid plays a vital role in prevention and treatment, covering 72 million Americans – including 20 percent of U.S. adults and 40 percent of children. Yet, many struggle to afford care. In 2021, the CDC found that 16 percent of insulin users rationed their supply due to cost, putting them at risk for severe complications — including kidney failure.

Cuts to Medicaid will reduce access to early diabetes screening and treatment, leading to more insulin rationing, uncontrolled diabetes, and inevitably, more kidney failure.

Diabetes: a preventable condition deeply shaped by social context

Type 2 diabetes accounts for 90–95 percent of all diabetes, a preventable condition tied to social context: inadequate health insurance, toxic stress, food insecurity, lead contamination, and pollution. These burdens are deeply shaped by both race and class, beginning in young adulthood.

Those from minority communities – Asian, Hispanic, Native, and Black Americans – are between 1.5–3 times more likely to develop kidney failure. Nearly 60 percent of those waiting for a kidney come from minority communities. A diagnosis by age 40 – early-onset diabetes – triples the risk of kidney failure compared to those diagnosed later.

Already this crisis is deepening. When the COVID-era protections against Medicaid disenrollment expired in March 2023, roughly 20 million people lost health coverage.

The unintended consequence of cutting Medicaid will be shifting cost to the Medicare End Stage Renal Disease Program (1972) as more patients with insufficiently treated diabetes develop kidney failure, deepening our dependence on organ transplantation, which now includes the use of genetically modified pig organs. This path reflects a deep policy failure: We’ve chosen to fund the back end of disease while neglecting front-end prevention.

It also raises urgent ethical questions about how we care (or don’t care) for young people with diabetes, how we treat sentient animals, and what risks we are willing to accept as a society. Pig organs for transplantation may create a pathway for zoonotic infections, posing public health risks that extend far beyond individual patients.

Transplantation is a treatment, not a cure.

The cost of a kidney transplant in the first 6 months is $446,800. Complications include cancer, infection, cardiovascular disease, and new onset diabetes after transplantation (NODAT). Psychological challenges, including depression, PTSD, and suicide, are common.

Outcomes for diabetic transplant recipients are often poor. Failed transplants—a common and tragic event—rank fourth as the cause of dialysis initiation; and, they represent a costly systemic failure: $1.38 billion a year. Today, 14 percent of those waitlisted are for a second or third transplant.

Policy choices

The Indian Health Service achieved a 54 percent reduction in kidney failure by integrating diabetes and kidney care in community clinics. This success can and should be replicated nationally.

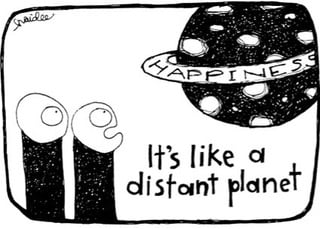

By focusing so intently on transplantation, have we redefined the diabetes pandemic as an organ shortage crisis, emphasizing the dreaded complication of kidney failure, but not the cause?

We are drowning in a surge of preventable diabetes complications and skyrocketing costs of the Medicare End Stage Renal Disease Program. We cannot afford to transplant our way out of this burgeoning disaster, nor should we want to.

The insidious trajectory of “diabetes-to-kidney-failure” can be minimized and even prevented. We must reduce demand for organs by treating diabetes early, ubiquitously, and comprehensively. Ultimately, this will lead to more organs available for those with unpreventable kidney failure and create a healthier, happier future for Americans.

Jane Zill is a psychotherapist.

Illustration credit: Haidee Soule Merritt

![Bureaucracy now consumes most of your health care spending [PODCAST]](https://kevinmd.com/wp-content/uploads/Design-3-190x100.jpg)