Just as society has been transformed by technology solutions driven by connectivity and ubiquitous information, medical practice is undergoing a digital transformation that was accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Today’s medical students will practice in a world where technology is a more integrated part of health care; technology and innovation should become a cornerstone of medical education and training. This proactive approach will prepare future physicians for the technology-driven health care landscape, not only as end-users but also as active builders of the very solutions they will be asked to use. We believe it is time for a medical curriculum 2.0, in which we weave the framework of innovative thinking into medical education.

There is an urgent need for better solutions to ongoing issues in health care. Physician burnout is at an all-time high. Patient distrust and medical misinformation are on the rise. The health-tech and med-tech space has seen an increase in startups and voices geared toward being the change, but not all have achieved success. New technology solutions that aim to address physician workload and improve patient experiences often fall short of their promises due to a lack of understanding of requirements and elements necessary to ensure product-market fit. Future physicians must learn how to interact with technology developers, communicate needs in the appropriate language, discern the feasibility of solutions, and understand the landscape of innovation. The imbalance in expectations and deliverables in innovation can be addressed by implementing a new medical curriculum that brings medical students and professionals into the product development cycle, bridging the gaps between conceptualization and product development.

Consider the differences in how tech teams and medical professionals approach problem-solving. Often, when a tech team launches a product or platform, the initial version is a minimum viable product (MVP). While this is common in the tech industry, it is not an intuitive concept in the health care space. The MVP does not address every concern the project originally aimed to solve, but it caters to the most critical user stories and streamlines core problems. Future iterations refine the product, but each phase takes time. This “imperfect, but viable” approach contrasts sharply with the “perfect” approach in which medical students are trained. This is not to suggest that one should replace the other, but rather that both ways of thinking should be taught. Bridging this gap in understanding will enhance collaboration and set clear expectations in every innovation-driven endeavor. We envision a curriculum that integrates opportunities for medical students and residents to learn the MVP approach and apply a model of experimentation to solving clinical workflow and patient care challenges.

As an example, one of the authors (RJ) observed the benefits of collaboration between technology and patient care at a local free medical clinic in California. The clinic applied principles of agile management, such as Kanban boards and sprints, to track workflow and tasks during remote clinic days while serving uninsured and underinsured patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. This collaboration between tech leads and clinic staff enabled the delivery of continuous care to patients affected by a digital divide that the pandemic exacerbated. Implementing methodologies not traditionally associated with medicine when adopting new tools can drive equitable solutions.

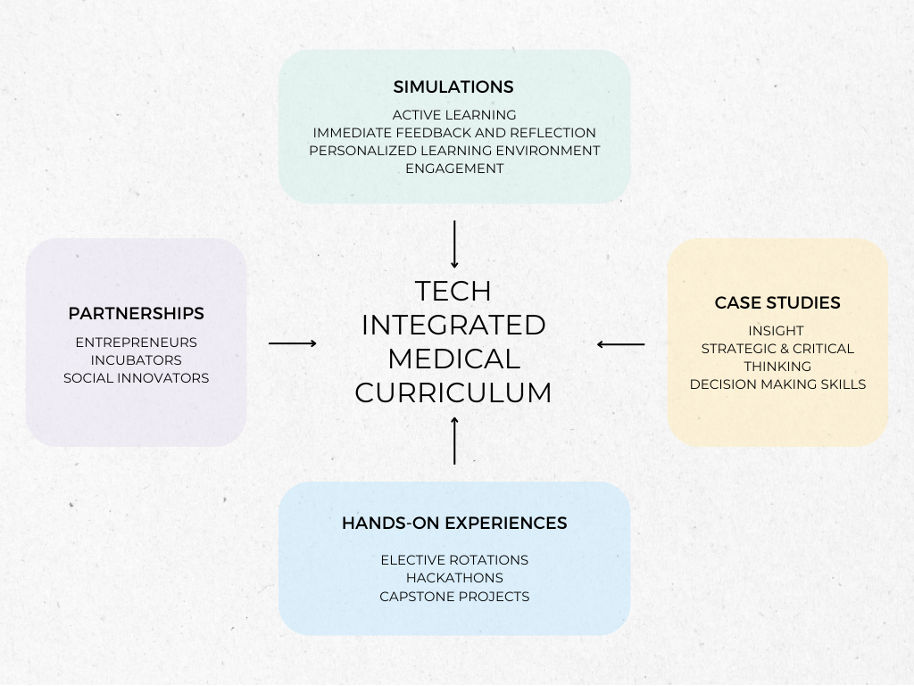

Medical education will thrive with an updated core curriculum and the standardization of an evolved technology curriculum. Responsible digital health solutions must invite members of communities that face a digital divide, including minority medical students, to bridge the health care delivery gap widened by health tech solutions, further supporting the standardization of a technology curriculum. To provide the greatest value to students and health care as a whole, partnerships with entrepreneurs, incubators, and social innovators will improve the development of high-quality products and enhance transparency in the innovation process. Coupling this with hands-on experiences such as elective rotations, hackathons, or capstone projects offers a balanced blend of theory and practice. Rather than expecting medical educators to remain at the forefront of every health-tech and med-tech advancement, schools can ensure students learn directly from leaders in technology. While case studies provide valuable insight, nothing compares to real-world experience. Who better to learn from than teams embedded in the future of health care technology?

To address the many health care challenges that require patient-centered, integrated, innovative, and adaptable solutions, it should be a priority to equip future physicians with the tools necessary to contribute to all aspects of change. A medical curriculum infused with simulations, case studies, partnerships, and more will cultivate skilled contributors to patient care decisions. Tomorrow’s solutions demand that today’s medical students play active roles in shaping the future of medicine and technology integration. It is time to take charge of this evolution, moving away from a traditional paradigm by updating the medical school curriculum.

Figure 1: Framework for a technology-integrated medical curriculum to prepare future physicians.

Rishma Jivan is a medical student. Omar Lateef and Bala Hota are physician executives.

![Orthorexia nervosa turns healthy habits into a harmful obsession [PODCAST]](https://kevinmd.com/wp-content/uploads/Design-4-190x100.jpg)

![Bureaucracy now consumes most of your health care spending [PODCAST]](https://kevinmd.com/wp-content/uploads/Design-3-190x100.jpg)