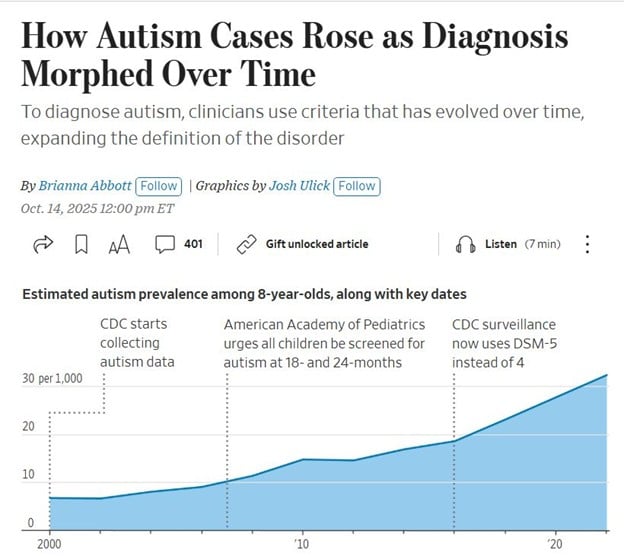

A recent Wall Street Journal graphic traces the rise in autism prevalence among eight-year-olds from 2000 to 2020. The slope is unmistakable, upward, steady, and steep. But it’s not a crisis. It’s a reckoning.

Each inflection point on that chart marks a milestone in institutional clarity:

- 2000: The CDC begins formal autism surveillance.

- 2007: The American Academy of Pediatrics urges universal screening at 18 and 24 months.

- 2013: DSM-5 replaces DSM-IV, collapsing subtypes into a unified spectrum.

This isn’t diagnostic inflation. It’s diagnostic evolution. The numbers rose because we finally looked. We widened the lens. We stopped pretending that silence was neutrality.

Before the ledger began

Before the CDC launched systematic surveillance in 2000, autism prevalence was a patchwork of local studies. Some regions reported rates as low as 1 in 2,500, others as high as 1 in 500. Without uniform criteria, families were left in limbo. The slope we see today begins with that moment of national reckoning, when surveillance became standardized, when the invisible became visible, and when prevalence became a matter of public record rather than rumor or denial.

Surveillance as moral infrastructure

As a developmental pediatrician who led NIMH-RUPP trials, I’ve seen how surveillance saves lives. It doesn’t inflate prevalence; it reveals presence. It doesn’t manufacture disability; it dignifies it.

This is a call to protect surveillance integrity from political sabotage. Surveillance is under attack, not by scientists but by demagogues.

Phoenix was the crucible.

During my tenure at the Arizona Child Study Center in Phoenix, the Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network at the University of Arizona reviewed my reports for inclusion in the CDC’s database, helping estimate ASD prevalence nationwide. The number of diagnosed Hispanic children surged.

Despite my limited Spanish, I leaned on our medical assistants for translation. Most of my patients were on Medicaid, reinforcing my commitment to closing health disparities. These families had long been invisible to the system. My evaluations made them visible.

The numbers spoke for themselves:

- 2002: ASD prevalence among Hispanic children stood at 3.4 per 1,000.

- 2004: 7.4 per 1,000.

- 2006: 8.3 per 1,000.

- 2010: 10.6 per 1,000.

- 2022: 32.2 per 1,000 (nearly ten times the rate recorded in 2002).

Everyone knew I was behind the surge in ASD diagnoses, but only the parents cared. One mother, speaking through our medical assistant, told me she had been dismissed by three clinics before arriving at ours. Her son’s behaviors were chalked up to “language delay” or “cultural difference.” When I explained autism, she cried, not from fear, but from relief. For the first time, someone named what she had seen all along. That moment reinforced why surveillance matters: It transforms invisibility into recognition.

Equity in the numbers

The surge in Hispanic prevalence wasn’t evidence of epidemic; it was evidence of equity. For decades, minority children were underdiagnosed, their families underserved. Surveillance corrected that imbalance. By 2022, Hispanic prevalence approached parity with White children, proving that when systems look, disparities shrink. That’s the slope we must defend. The numbers are not just epidemiology; they are moral testimony.

The politics of unreasonable doubt

And here’s the irony: The chart that rebukes conspiracy rhetoric was published in The Wall Street Journal, the conservative newspaper of choice. Rupert Murdoch’s flagship. Not exactly a bastion of progressive epidemiology. Not part of any imagined “deep state.” Just data. Just graphics. Just truth.

Robert Kennedy Jr. and Donald Trump tend to focus less on data and more on public sentiment. They often use uncertainty to raise doubts and portray established diagnostic conclusions as questionable. Their messaging extends beyond skepticism about vaccines and reflects a broader challenge to established sources of information.

When they call autism a “manufactured epidemic,” they erase every child I’ve ever diagnosed in Phoenix. When they call surveillance “government overreach,” they undermine the very systems that protect our most vulnerable.

This isn’t about politics. It’s about presence. It’s about the slope. It’s about the children who were invisible until surveillance made them visible.

A call to clinicians and coalitions

Clinicians cannot stand alone. Legislators must fund surveillance. Families must demand it. And editors must publish it without sanitization. The slope is not just epidemiology; it is moral infrastructure.

If we allow populist rhetoric to erode it, we will return to the era of invisibility. That is a betrayal of every child whose diagnosis was hard-won. Surveillance is not optional. It is the scaffolding of dignity.

We must defend the slope. Not as data, but as presence. Not as prevalence, but as justice. Because if we don’t, the next chart won’t show prevalence. It will show erasure. And history will not forgive us for silence.

Ronald L. Lindsay is a retired developmental-behavioral pediatrician whose career spanned military service, academic leadership, and public health reform. His professional trajectory, detailed on LinkedIn, reflects a lifelong commitment to advancing neurodevelopmental science and equitable systems of care.

Dr. Lindsay’s research has appeared in leading journals, including The New England Journal of Medicine, The American Journal of Psychiatry, Archives of General Psychiatry, The Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, and Clinical Pediatrics. His NIH-funded work with the Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology (RUPP) Network helped define evidence-based approaches to autism and related developmental disorders.

As medical director of the Nisonger Center at The Ohio State University, he led the Leadership Education in Neurodevelopmental and Related Disabilities (LEND) Program, training future leaders in interdisciplinary care. His Ohio Rural DBP Clinic Initiative earned national recognition for expanding access in underserved counties, and at Madigan Army Medical Center, he founded Joint Base Lewis-McChord (JBLM) CARES, a $10 million autism resource center for military families.

Dr. Lindsay’s scholarship, profiled on ResearchGate and Doximity, extends across seventeen peer-reviewed articles, eleven book chapters, and forty-five invited lectures, as well as contributions to major academic publishers such as Oxford University Press and McGraw-Hill. His memoir-in-progress, The Quiet Architect, threads testimony, resistance, and civic duty into a reckoning with systems retreat.

![Stopping medication requires as much skill as starting it [PODCAST]](https://kevinmd.com/wp-content/uploads/The-Podcast-by-KevinMD-WideScreen-3000-px-4-190x100.jpg)

![Weaponizing food allergies in entertainment endangers lives [PODCAST]](https://kevinmd.com/wp-content/uploads/The-Podcast-by-KevinMD-WideScreen-3000-px-3-190x100.jpg)

![AI censorship threatens the lifeline of caregiver support [PODCAST]](https://kevinmd.com/wp-content/uploads/Design-2-190x100.jpg)